This article was published in Qui Parle, spring/summer 2011 vol.19, no.2

Painting the Animals

For twenty-two years I have been concerned with the exploitation

of animals. For twenty-eight (my whole life), I have been disabled.

For the past few years I have been painting images of animals

in factory farms. The following essay was born from this visual

artistic practice.1 My paintings not only led me to research; they

forced me to see and focus on animal oppression for hours every

day in a way I never had before. Through this focus I became increasingly

aware of the interconnections between the oppression

of animals and the oppression of disabled people. This connection

did not lie, as many people suggested, in my being confi ned to my

disabled body, like an animal in a cage. Far from this, the connection

I found centered on an oppressive value system that declares

some bodies normal, some bodies broken, and some bodies food.

The Freak and the Patient

my life I have been compared to many animals. I have been told

I walk like a monkey, eat like a dog, have hands like a lobster, and

generally resemble a chicken or penguin. These comparisons have

been said out of both mean-spiritedness and a spirit of playfulness.

As a child I remember knowing that when my fellow kindergarten

classmates told me I walked like a monkey, that they meant it to

hurt my feelings, which of course it did. However, I wasn’t exactly

sure why it should hurt my feelings—after all, monkeys were my

favorite animal. I had dozens of monkey toys. My parents recall

that my favorite thing as a toddler was to go to our local miniature

golf course to see the giant King Kong. I was small enough that I

could sit in the concrete gorilla’s open palm. Still, I knew that when

the other children compared me to a monkey, they were not doing

it to fl atter me. It was an insult. I understood that they were commenting

on my inability to stand completely upright when out of

my wheelchair—my inability to stand straight like a normal human

being. I understood that saying I was like an animal separated

me from other people. Whether I considered if the statement meant

that I was less than human, I don’t remember.

The thing is, they were right. I do resemble a monkey when I

walk—or rather I resemble an ape, specifi cally a chimpanzee. My

standing posture is closest to the second or third fi gure on a human

evolution diagram—certainly not the last. This resemblance is simply

true, as is the statement I eat “like a dog” when I don’t use my hands

and utensils to eat. These comparisons have an element of truth that

isn’t negative—or, I should say that doesn’t have to be negative.

When I ask members of the disabled community whether they

have ever been compared to animals because of their disabilities,

I receive a torrent of replies. I am transported to a veritable bestiary:

frog legs, penguin waddles, seal limbs, and monkey arms. It

is clear, however, from the wincing and negative interjections that

these comparisons are not pleasant to remember.

Animal comparisons abound in disability history—most explicitly

in the stage names of the world’s famous freaks. There was

Otis the Frog Boy, Mignon the Penguin Girl, Jo-Jo the Dog Faced

Boy, Darwin’s Missing Link, and of course the Elephant Man. In

sideshow culture, disability oppression crashed head-on into racism,

sexism, classism, and I would say, speciesism. Looking through

old medical textbooks and dictionaries, I see that the comparisons

have existed within medical discourse as well—elephantitis, ape-

hand syndrome, lobster-claw syndrome, pigeon chest, goosebumps,

chickenpox, and phocomelia (seal-like limbs), to name just a few. In

medical history, gender and racial lines were also often clearly delineated

as markers of normalcy and deviance, creating a standard

of human physiology that normalized whiteness and often animalized

people of color, while simultaneously pathologizing those who

physiologically and culturally defi ed accepted gender dichotomies

and roles. Teratology (the study of congenital disabilities—literally

the study of monsters) placed disability clearly within the category

of deviance. Teratology seemed to ask, which monsters do we count

as human, and which monsters are more like animals?

These animal comparisons exist in both sideshow culture and

medical discourse, which are two of the main fi lters through which

disability is still perceived today. Although only a few sideshows

remain in the United States, their tantalizing aesthetic continues as

a cornerstone of exoticism and camp. In many ways I am drawn to

the allure of the sideshow just as many people are; it is seductive.

The sideshow freaks’ charm and brilliance was in their showmanship.

If only I were to look as exceptional as one of them when I

perform my daily chores! The freaks had to embody their stage

names—if Mignon the Penguin Girl’s livelihood depended on her

embracing and exaggerating her penguinness, then she would wear

clothes that drew attention to certain aspects of her shape and

“waddle.” It is easy for me to romanticize the sideshow, fantasize

about their radical bohemian lives, and dream about the solidarity

and communities they must have had. But the sideshows were

no doubt complicated, abusive, and oppressive realities also, made

even more hideous by racism and sexism. And, of course, they

were virtual zoos, where people paid to wander from one exotic

beast to the next.

Despite the abundance of good medicine, I have few romantic

fantasies about hospitals. Disability studies calls the co-opting of

disability in the early 1900s by the medical profession “the medical

model of disability.” Disability went from being a moral, spiritual,

or metaphysical issue to a medical one. Where disability had once

been understood as an intervention by God or as the price paid

for a karmic debt, it was now understood as medical deviance. Al-

though in many ways this shift in discourse was better for disabled

individuals, it has also been problematic. The medical model of

disability positioned the disabled body as working incorrectly, as

being unhealthy and abnormal, as in need of cure. Rosemarie Garland

Thomson writes, “Domesticated within the laboratory and

the textbook, what was once the prodigious monster, the fanciful

freak, the strange and subtle curiosity of nature, has become today

the abnormal, the intolerable.”2 With this medical and scientifi c

colonization, the disabled body “demand[s] genetic reconstruction,

surgical normalization, therapeutic elimination, or relegation

to pathological specimen” (“FWE,” 4). Doctors probe, measure,

and stare, but as the joke often goes, “at least the freaks got paid.”

In hospitals, one is supposed to feel grateful for this invasion—

doctors are experts who can cure or care for us—but doctors do

not own the atypical body any more than P. T. Barnum did. The

medical profession’s gaze on disability is calculated, measuring, labeling,

and dissecting. The disabled person becomes a body to be

cropped, numbered, and labeled—not unlike a butcher’s diagram.

What does it mean to be compared to an animal? To be called a

“Monkey Woman”? Is there any way to consider these metaphors

beyond the blatant racism, classism, and ableism these comparisons

espouse? I fi nd myself wondering why animals exist as such

negative points of reference for us, animals who themselves are victims

of unthinkable oppressions and stereotypes. In David Lynch’s

1980 classic Elephant Man, John Merrick yells out to his gawkers

and attackers, “I am not an animal!” Freaks and patients are often

treated as such during their lives, “handled” by both freak-show

operators telling them how to perform and by doctors directing

them how to move so that they can be more easily inspected. No

one wants to be treated like an animal.3

But how do we treat animals? We treat animals as things to be

used for our benefi t—we watch them in zoos, gawking at their different

bodies, their different ways of moving and acting. We label

and number their body parts for purposes like meat, milk, and

leather. In short, we treat them as if their bodies exist solely for

us. As a freak, as a patient, I do not deny that I’m like an animal.

Instead, I want to be aware of the mistreatment that those labeled

“animal” (human and nonhuman) experience. I am an animal.

A friend of mine who has osteogenesis imperfecta (or “brittle

bones”) shared with me that while she was growing up her mother

told her she had a camel walk. “This was her label for me walking

with my hands and legs on the ground—with my bum in the air

like a camel hump. It never bothered me and I’d say I had camel

pride.” However, she went on to say, “I didn’t like being told by

my stepdad that I had arms like a monkey (they look long in comparison

to my body because they haven’t been broken as much as

my legs).” Why was the monkey comparison offensive, whereas

the camel was not? Was it because being compared to a monkey

has so much more historical baggage than being compared to a

camel (at least in Western culture)?

Some animal comparisons are no doubt more troubling than

others. In sideshows, the more truly disturbing comparisons were

left for people of color and the cognitively disabled. These were the

freaks who were displayed as missing links and as not quite human,

reinforcing and justifying extremely racist stereotypes. These freaks

were “What Is It?”; “Maximo and Bartola, the Aztec Twins”; “The

Missing Link”; and “Krao, the Ape Girl.” These are the animal

metaphors that epitomize what’s wrong with animal metaphors.

We hear phrases like “monkey girl” or “dog boy” and think of

oppression. Being compared to an animal is negative largely because

of history and culture, because of the discrimination such comparisons

engender against human beings. But what of the chimpanzees

and orangutans, elephants and tigers, dogs and other “beasts” who

were displayed alongside the sideshow freaks? Animals who themselves

were trapped and taken from their environments and trained

to perform tricks? Animals who, to this day, perform with Barnum

and Bailey Circus, where regular beatings force them to perform

and they are never again to see their natural environments?4 What

of these animals? Are they similar to us in any way that matters?

Are their oppressions similar to our oppressions?

I argue that at the root of the insult in animal comparisons is a

discrimination against nonhuman animals themselves. These nonhumans,

one large mass of greatly varying beings, are held together

by one similarity—they aren’t us. No matter how aware, sentient,

or intelligent, they are the ultimate other. The disabled are in many

ways a close second. We are the world’s

largest minority. We come in all colors, genders, nationalities, economic

and cultural backgrounds; and on top of this we are “freaks

of nature,” “monstrosities,” “beasts,” “abnormal,” “broken.”

I acknowledge that I am entering into slippery territory with the

writing that follows, territory in which terrible oppressions have

found footing. For although I have not directly mentioned them,

there is no way to discuss animal metaphors without recognizing

the atrocities that they have been used for: the rhetoric of Nazi

Germany, of racism, of slavery. And the rhetoric of the sideshow

was hardly better, clearly using animal comparisons to support racist

ideologies and demeaning and patronizing stereotypes. So why,

when so many people, myself included, have felt the negative and

hurtful consequences of being compared and associated with nonhuman

animals, would I enter this territory?

The simple answer is that I do it because more than 50 billion

animals die every year for human interests.5 They die for food, science,

fur, for products, entertainment, and sport. They die for these

uses because they aren’t human and because we can’t seem to fi gure

out what our ethical responsibilities toward them are. I argue

that many of the experiences of disabled people and much of the

work done in disability studies can help us to understand animal

oppression differently. By showing how disability studies reevaluates

the meanings of terms such as “independence,” “nature,” and

“normalcy” and by exploring the ways in which disability studies

demands new perspectives on embodiment, this essay will argue

that disability studies could have a positive and powerful affect on

the animal rights discussion.

I take a risk in exploring the parallels between disability oppression

and animal oppression, because this risk seems necessary

to challenge predominant themes and arguments that support the

continued exploitation of animals and of disabled people.

Independence, Nature, and Normalcy

Disability studies argues for realizing new ways of valuing human

life that aren’t limited by specifi c physical or mental capabilities.

We argue that it is not specifi cally our intelligence, rationality, agility,

physical independence, or bipedal nature that give us dignity

and value. We argue that life is, and should be presumed to be,

worth living, whether you are a person with Down syndrome, cerebral

palsy, quadriplegia, autism, or like me, arthrogryposis. Many

disability activists and scholars go further than this, arguing that

even those that are deemed to be severely and irrevocably braindamaged

have a right to a life of respect and dignity.

This is not just some trite declaration of pride or a romantic

statement on the sanctity of human life; rather, our reclaiming of

value comes from the recognition that much of what disabled people

can offer society has been undervalued or has been considered

detrimental by a culture invested in certain bodies and certain ways

of doing things. Paul Longmore, a disability studies writer and historian,

writes: “Beyond proclamations of pride, deaf and disabled

people have been uncovering or formulating sets of alternative values

derived from within the deaf and disabled experience. . . . They

declare that they prize not self-suffi ciency but self-determination,

not independence but interdependence, not functional separateness

but personal connection, not physical autonomy but human community.”

6

At their roots, all arguments used to justify human domination

over animals rely on comparing human and animal abilities

and traits. We humans are the species with rationality, with

complex emotions, with two legs and opposable thumbs. Animals,

lacking certain traits and abilities, exist outside our moral responsibility.

We can dominate and use them, because they are lacking

certain capabilities. But if disability advocates argue for the protection

of the rights of those of us who are disabled, those of us

who are lacking certain highly valued abilities like rationality and

physical independence, then how can disability studies legitimately

exclude animals for these reasons without contradiction? I argue

that disability studies has accidentally created a framework of justice

that can no longer exclude other species.

None of this is to say that abilities and variations in abilities do

not matter. Clearly, there are important differences between the

abilities of a conscious human being and someone who is braindead.

Clearly, there are differences between the abilities of a squirrel

and the abilities of a lettuce plant. To me, and to most animal

rights activists, the one ability that is a prerequisite for moral consideration

is sentience. Sentience is what sets us apart from computers;

it’s what sets human and nonhuman animals apart from

plants. Sentience is the ability to feel, to experience, to perceive.

Animals are physiologically very similar to us. Even fish, whose

capacities to feel are far too often disregarded, have physiological

reactions to pain that are similar to those of human beings and

react to painkillers as a human would.7 It is impossible to ignore

the immense amount of evidence that shows that the animals we

exploit are sentient, which means that they are able to experience

feelings—pleasurable ones and painful ones.8

The following questions thus must be asked: If an animal is living its own life, feeling

pain and pleasure, perceiving and experiencing, do we have an

obligation to avoid causing unnecessary harm to that animal? Furthermore,

do we have an obligation to acknowledge that animal’s

right to her own life—a life that she alone is experiencing? Do we

have an obligation to try to coexist rather than to exploit?

My work builds on Martha Nussbaum’s Frontiers of Justice,

which shows how the tradition of the social contract has failed to

provide substantial groundwork for justice for not only disabled

people and nonhuman animals, but for human beings of different

nationalities around the world.9 The idea of the social contract, “in

which rational people get together for mutual advantage, deciding

to leave the state of nature and to govern themselves by law” (FJ, 3),

fails to address these areas of justice, as it assumes that in a “state

of nature” “the parties to this contract really are roughly equal in

mental and physical power.”10 Of course, as Nussbaum points out,

this assumption does not take into consideration physical asymmetry

between men and woman, let alone between the disabled and

the able-bodied, or between humans and nonhumans. Although

many animals are physically powerful, Nussbaum points out that

we still dominate them, “and the whole point of the state of nature

was to say that no one can really dominate . . . but with nonhuman

animals, we dominate them. We have totally won that battle”

(“JU,” 122). Nussbaum’s work also explores how the idea of mutual

advantage falls short when addressing disability and “species

membership” as disabled individuals and animals don’t necessarily

offer any mutual advantage (and in some cases may offer a disad-

vantage). Thus Nussbaum argues that a more complete theory of

justice must include other, more complex reasons for human cooperation

besides advantage, such as love, compassion, and respect.

Nussbaum shows how the physical vulnerability of disabled

individuals and animals is immensely problematic under a social

contract tradition of justice, because even in a “state of nature” an

asymmetry in power exists between these groups and able-bodied

human beings. Nussbaum thus argues that “the classical theory

of the social contract cannot solve these problems” (FJ, 3), as the

problems are built into the theory’s foundations, and thus new theories

are needed.11

An interesting parallel to Nussbaum’s critique of the social

contract is available in another contract theory that has recently

gained popularity among those who support eating sustainably

and humanely produced animal products. This theory says that

human beings and domesticated animals have entered into a contract

with each other that, like the social contract theory, is largely

based on the idea of mutual advantage.12 The second half of this essay

will explore and critique this theory and show how it fails as an

argument for continued animal exploitation, as the contract itself

is based in asymmetrical foundations and the rules of the contract

are themselves unequal.

Nussbaum’s work on the idea of vulnerability is also relevant to

the remainder of this essay, as I argue that vulnerability is closely

related to an idea of dependence that is problematic for both disabled

people and animals. Those who are vulnerable are also often

dependent, and this dependence can easily become an excuse for exploitation.

Viewing the concepts of dependence and independence

through a disability studies lens can add signifi cant strength to the

arguments for animal rights and disability rights in these debates.

Disabled people are negatively affected by limited interpretations

of the concept of independence, and disability studies has

worked to redefi ne what independence can mean. Independence,

I argue, is more about choice and civil rights than it is about pure

self-sufficiency. Like Paul Longmore, I argue that it is interdependence,

not independence, and community, not physical autonomy,

that should be supported and recognized as essential for sustaining

a just society.

In American rhetoric there is a strong emphasis on independence

and self-suffi ciency. America is the country where everyone has the

opportunity to become “independent.” Independence is perhaps

prized beyond all else in this country, and for disabled people this

means that our lives are automatically seen as tragically dependent.

Michael Oliver, like many disability theorists, argues that

dependence is relative: “Professionals tend to defi ne independence

in terms of self-care activities such as washing, dressing, toileting,

cooking and eating without assistance. Disabled people, however,

defi ne independence differently, seeing it as the ability to be in control

of and make decisions about one’s life, rather than doing things

alone or without help.”13 We as a society are all dependent on each

other. The difference between the way the disabled community sees

dependence and how the rest of society views it is that there is not

so much emphasis on individual physical independence. Today, independence

is more about individuals being in control of their own

services (be it education, plumbing, electrical, medical, dietary, or

personal care) than it is about individuals being completely physically

self-sufficient; this is true not only for the disabled population

but for the population in general.

A large part of the stigma attached to being disabled is that

those who are physically dependent are seen as burdens. The more

impaired someone is, the more of a burden he or she is. Disability

scholars argue, however, that the only reason why many people are

a (perceived) burden on their family and friends is that they have

such limited options.14 Disability rights activists and scholars argue

that, in our society, it is not the impairment that is the reason

for dependence; it is our impaired system of social services. I have

countless friends whom society would no doubt label as burdensome

and dependent—not to mention myself (I use a wheelchair

and have very limited use of my arms). And yet, these friends and

colleagues are some of the most directed, productive, and creative

people I know, despite the fact that many use and rely on attendants

and other support services.

For animals, dependence is what allows and even excuses their

exploitation by humans. This is seen in much of the philosophy

behind the humane meat movement. Authors such as Michael Pol-

lan and Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall argue that to be vegetarian or

vegan would mean abandoning those animals who are most dependent

on us.15 Leaving them to their own devices, they say, would

be a fate far worse than the dinner table. The theory they follow

says that we have entered into a co-evolutionary pact with these

species that gives us the responsibility to care for them in exchange

for their services and fl esh. Some vegetarians and vegans respond

by arguing that human beings should stop breeding these animals

and let their species go extinct. They argue that the dependency of

these species makes them so vulnerable to human exploitation that

to keep these species surviving is irresponsible.

Is there another way? What would a reframing of dependency

look like to animals oppressed by humans? Viewing the dependence

of farm animals through a disability studies framework gives new

answers to the questions surrounding animal exploitation and may

also open up a third path. Instead of continuing to exploit animals

because they are dependent on us, and instead of leading these animals

to extinction as a potential vegan alternative, could we not

realize our mutual dependence on each other, our mutual vulnerability,

and our mutual drive for life? The big questions in disability

studies seem equally relevant to the animal rights debate: How can

we create new meanings for words like “dependent” and “independent”?

How can those who are seemingly most vulnerable within

a society be perceived as also being useful, strong, and necessary?

Along with dependency, the other two concepts that I argue are

of great importance to both the fields of disability studies and critical

animal studies are “nature” and “normalcy.” The phrase “the

natural cycle of things” has been used to justify everything from

infanticide of disabled babies to the continued slaughter of animals

for food. The idea of nature and what is natural has led to

discrimination toward disabled people and the medicalization of

the concept of disability, while at the same time it has been used as

proof of our right to eat and use animals.

Within certain social justice movements (especially those surrounding

food), there is a certain romanticization of nature—currently

very popular—that often leaves out certain bodies, including

the disabled body. It is a romanticization of “how things used to

be” and “how things are in nature” that often ignores that things

were not necessarily as good for some as they were for others and

that an idea of nature is diffi cult, if not impossible, to separate from

human culture and paradigms. Just as the social contract tradition

has failed to recognize the inequality that exists in a so-called state

of nature, so does this idea of nature fail to see the power inequalities

that exist within it.

Nature is one of the most common and compelling rhetorical

tools used by those who justify animal exploitation. Arguments

range from nuanced discussions of sustainable farming to passionate

declarations that animals eat other animals in nature, and that in

any case, nature is simply “red in tooth and claw.” Nicolette Hahn

Niman, author of The Righteous Porkchop, writes, “Clearly it’s

normal and natural for animals to eat other animals, and since we

humans are part of nature, it’s very normal for humans to be eating

animals.”16 But violent, painful deaths are also “normal and natural”

in nature. Would Niman use that fact to argue that we have no

moral obligation to kill animals humanely? What about human-onhuman

violence? That’s certainly “natural.” But is it ethical?

Patriarchy and disability oppression are also interesting parallels

to this way of thinking. Throughout history and in virtually all

cultures, patriarchy in some form has been the norm, and disability

oppression and marginalization has existed. Of course there have

been a few scattered cultures here and there that treated woman

and disabled people more fairly than others, but the same can be

said of our treatment of animals. Patriarchy is not something we

should accept as natural–and neither is a paradigm of able-bodied

superiority or of human domination over animals.

I argue that appealing to nature as a justifi cation for ethical belief

is a fallacy, and it has been used historically to justify every

conservative power structure. Other animals, with no alternative

sustenance, often with specifi c dietary requirements, and with

varying cognitive abilities regarding such things as empathy, do

not seem to be appropriate role models for our ethical lives. We are

animals that have evolved to recognize other beings’ subjectivity,

to experience empathy, and to make ethical choices. If a desire for

meat is in human nature, it must be remembered that it is also in

human nature to question the way we live, to think about ethics,

and to change our habits as our moral lives change. We, unlike virtually

all other animals, choose what we eat.17

As a disabled person I fi nd ethical arguments based on what’s

“natural” to be highly problematic. If history reveals something

of “the natural cycle of things,” I would have been killed at birth

at worst or culturally marginalized at best. Many of my disabled

friends would not be alive if it weren’t for their parents and society

thinking differently about the “natural cycle of things.” This is not

to say that we shouldn’t look toward nature or history for ways

of behaving and living sustainably. Rather, it is simply to say that

we shouldn’t forget that these traditions often grew out of paradigms

of domination and oppression. As Nussbaum explains, human

dominance and power asymmetry still exist even in a so-called

state of nature.

Disability studies has been critiquing what medical discourse

views as natural and normal for years. For decades disabled children

and adults were pressured by the medical establishment to

receive surgical treatment that could potentially decrease abnormal

functionality (such as the functional use of a “deformed” limb)

but increase a more “normal” appearance. This is still a common

practice in regards to intersex children and other individuals whose

“deformities” are seen as especially taboo. But perhaps an even

more vivid example of how the medical profession’s ideas of nature

and normalcy affect disabled people and medical policy is in the

current debate surrounding infanticide. Many arguments in support

of infanticide point out that “in nature” disabled babies are

often killed or left to die and that we should let “nature run her

course”—meaning we should let the disabled baby die in peace or

even help him or her to die. This opinion is grounded in the idea

that it is simply natural to think disability is a bad thing—it is common

sense, everyone knows it.

The disability community argues that impairment is not naturally

a negative experience. This is not at all to say that being impaired

does not have negative aspects that are very real and often

diffi cult, but instead to say that cultural and political oppressions

deeply effect and are entangled with nearly all suffering that surrounds

being disabled. An inaccessible society that stereotypes and

misjudges impairment is very often far more frustrating than our

bodies are. Stairs are no more natural than ramps. Disability oppression

is not natural, and the idea that disability is a personal

tragedy as opposed to an issue of social justice needs rectifying.

Impairment can offer many valuable insights and experiences to

human society and culture. It is pointed out by disability activists

and scholars that most people, if they live long enough, will experience

disability at some point in their lives, or at least in old age.

If this vulnerability of the human body was more acknowledged,

perhaps disability and aging would be much less feared, as society

would adapt and come to expect and prepare for disability. Of

course, when most people think of disability as abnormal and in

need of a cure, they don’t think of their elderly grandparents; they

think of those of us with curved spines, or no limbs. They think of

the “freak of nature.”

Nature is currently an acceptable framework from which to critique

and classify disabled and animal bodies, whereas it is no longer

an acceptable endpoint for discussions of race and gender. This

double standard needs to be addressed and questioned. Discourses

of normalcy and the argument of “common sense” are also commonly

used to justify animal exploitation.18 In reevaluating what

is natural and “normal” regarding disabled people, does disability

studies not then ultimately demand a reevaluation of what is often

said to be the “natural cycle of things” regarding human domination

over animals? I argue that because disabled people and nonhuman

animals (especially domesticated animals) are viewed as dependent,

their treatment and place in society is more commonly

considered within (and more deeply affected by) conventional notions

of nature and normalcy than that of other populations.

In the second half of this essay I turn toward the question of

animal rights, in particular, the debate over humane meat, to show

more specifi cally how disability studies offers new ways to consider

our responsibility toward nonhuman animals. The ethics of

eating animal products is arguably the most pervasive and hotly

contested form of animal exploitation, and I focus on the debates

surrounding humane meat as the strongest and most compelling

direction of the conversation.

Fig. 1. Lobster Girl. Oil on xerox, 2” x 5”, 2009.

Fig. 2. Dead Calves on a Conveyor Belt. Oil on canvas, 5” x 4”, 2008.

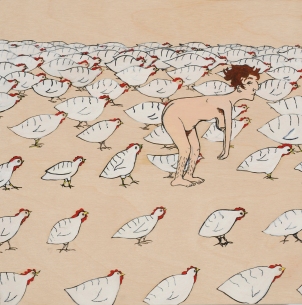

Fig. 3. Culled Male Chicks in a Dumpster. Oil on canvas, 5’ x 3.5’ (60” x 42”), 2008.

Fig. 3. Culled Male Chicks in a Dumpster. Oil on canvas, 5’ x 3.5’ (60” x 42”), 2008.

Fig. 4. Animals with Arthrogryposis. Oil on canvas, 6’ x 9’ (72” x 108”), 2009.

Fig. 4. Animals with Arthrogryposis. Oil on canvas, 6’ x 9’ (72” x 108”), 2009.

Animal Rights Today: The Humane Meat Argument

In my second year of graduate school in the Department of Art

Practice at the University of California, Berkeley, I began a painting

of discarded male chicks. The title of the painting was Culled

Male Chicks in a Dumpster (oil on canvas, 2008, 5’ x 3.5’). The

painting (see fi g. 3) is of hundreds of male chicks, maybe a day old,

who have been thrown in a dumpster alive, as they are completely

useless to the egg and meat industry. They are useless because

males don’t lay eggs and are not used for meat. The use value or

profi tability of these chicks is virtually zilch, so sometimes they

are simply thrown away. Sometimes they are spread alive or dead

on farms for fertilizer. Sometimes they will fi nd their way into dog

food, or sometimes they will be made into feed and fed back to

their sisters.

In factory farms, animals are never seen as individuals; they are

rarely even seen as animals. They are simply raw materials to be

transformed into product. In painting them, I hope to express what

they really are: alive and aware.

What does it mean to say something is alive? Is there a difference

between a dumpster full of uprooted tomato plants and one

fi lled with day-old chicks?

Most people, I believe, would say yes; clearly there is a difference

between the little birds and the rejected fruit, even though

both are alive. But what is this difference? An animal rights supporter

would say that as far as we can tell scientifi cally and biologically,

the tomatoes do not suffer. Chicks, on the other hand, are

biologically similar to us in that they feel pain; they are sentient.

One could say that we can’t be sure that plants don’t suffer, that

just because they are different from us doesn’t mean we should

count them out. Many thinkers have done a good job of giving

plants personalities (the most convincing being Michael Pollan’s

determined and adventurous corn in The Omnivore’s Dilemma),

and have shown how ingeniously plants have used us to their evolutionary

advantage. But however biologically ingenious plants

are, virtually no one, scientist or otherwise, claims that plants experience

pain and suffering.

Thus one dumpster is fi lled with beings that feel pain before they

die. They feel the cold or the heat. They feel the weight of others

on top of them. They feel hunger and thirst. The other dumpster is

fi lled with plants that have developed deterrents to being eaten or

who release different chemicals at different stages of their development,

but it is not fi lled with feelings.

Some may also say that to claim that chicks suffer is to be sentimental.

They may claim we are just anthropomorphizing these

birds that run on nothing but instinct, and that instinct is nothing

but nature’s equivalent to a computer or, as Descartes thought, the

mechanics of a clock. But the scientifi c evidence supporting animal

sentience is overwhelming and undisputable. Few people today

would condone the scientifi c experiments inspired by Descartes’

work, where hearts were cut out of fully conscious dogs, while

their cries were said to be nothing more than the equivalent of the

tick-tock of a clock.

The discussion on sentience used to focus mostly on the soul,

on who had souls and who didn’t. Throughout history, women,

the poor, and people of color sometimes had souls and sometimes

didn’t. Animals almost certainly were without souls, at least in the

Judeo-Christian tradition. Although many people would no longer

fi nd the concept of a soul to be a good justifi cation for giving

or denying rights, much of the current animal rights critique

is still rooted in this paradigm. Joel Salatin, the sustainable meat

farmer whom conscientious omnivores often reference (he’s profi

led by Pollan), is a prime example. When asked by Pollan “how

he could bring himself to kill a chicken,” Salatin replied, “That’s

an easy one. People have a soul, animals don’t. It’s a bedrock belief

of mine. Animals are not created in God’s image, so when they

die, they just die” (OD, 331). Salatin, however, does believe that

animals are capable of suffering and feeling pleasure, so he is opposed

to factory farming just as passionately as any vegan. His

animals genuinely seem to have a content life on his picture-perfect

Polyface Farm, but they are still killed after living only a fraction

of their natural life span. They are still bred by humans and are

legally property, two points that we’ll explore later on. Salatin also

still has to cull his male chicks, as they are just as useless to him as

they are to the large factory producers.

Another of my paintings, Dead Chickens on a Conveyor Belt

(oil on canvas, 2008, 4” x 5”), is an image of hens who have just

had their throats slit. If they are lucky they will bleed out and be

either dead or fully unconscious before hitting the scalding water

that removes their feathers. Whether at Salatin’s farm or at a factory

farm, this is almost always the way chickens die—upside down

with a knife to their neck, their feet held either by a metal conveyor

belt or by hands they have grown to trust as bearers of food, shelter,

and warmth. For the hen in the factory farm, who has never

known anything but neglect and cruelty, the treatment at the end

of her life is sadly in line with all she has known; for the hen at a

family farm like Salatin’s, however, it is a wholly new experience.

Do animals deserve equal consideration? Do their experiences

matter?

Imagine this scenario. What would Joel Salatin do if he lost his

faith and no longer believed in souls? Salatin would then find himself

asking our question: Do animals deserve equal consideration?

Potentially Salatin might become a vegan. A more likely scenario,

considering the fact that he makes his living by raising animals

for meat, is that he’d look to other farmers and writers for ethical

advice. He quite possibly would fi nd Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall.

Fearnley-Whittingstall is similar to Salatin in that he practices

sustainable, grass-based farming while also trying to minimize his

animals’ suffering. However, for Fearnley-Whittingstall, religion is

not a good enough justifi cation for killing animals, and neither is

tradition, history, or taste. In fact, the fi rst few pages of “Meat and

Right,” the fi rst chapter of his cookbook The River Cottage Meat

Book, reads like a vegan manifesto. For pages he tears apart every

argument commonly heard for why eating animals is justifi ed. One

would hardly believe that the same book contains recipes for pork

chops and smoked sheep liver. Fearnley-Whittingstall is no vegan.

He is, however, not afraid of the debate. He argues that the right

to breed, raise, and kill animals comes from nature itself and from

evolution. Fearnley-Whittingstall condones killing largely because

of the contract theory of co-evolution. This contract with domesticated

farm animals, he says, gives us not only a right but a responsibility

to kill animals for food.19 This argument may sound familiar,

as Pollan argues the same thing in The Omnivore’s Dilemma.

The theory says that if we look at things in evolutionary terms,

domesticated animals are doing remarkably well. Their populations

are high and spread all around the globe, and they have another

species—humans—providing them food and shelter. The theory

argues that the relationship of domestication—and the killing

that goes along with it—is just as benefi cial for the animals as it is

for the humans. After all, if we didn’t eat them, they wouldn’t exist.

“From the animals’ point of view,” Pollan writes, “the bargain

with humanity turned out to be a tremendous success, at least until

our own time. Cows, pigs, dogs, cats, and chickens have thrived,

while their wild ancestors have languished” (OD, 120). Thus we

have entered into a sort of social contract with these species, based

on supposed mutual advantage; we provide and care for them, and

in return they feed our soil and give us their fl esh. To be vegan

would be to turn our back on this relationship and send these dependent

domesticated animals out into the wild, where they would

die of starvation or be brutally killed by other animals.

“It is not only the death of our farm animals over which we

have such complete control,” says Fearnley-Whittingstall. “It is

also their birth, and their life. We breed them and we feed them;

and after we kill them, they feed us. In this sense, the relationship

is undeniably symbiotic. And such is the success of the symbiosis

that, along with ourselves, our sheep, cattle, pigs, and poultry are

among the most ‘successful’ species on the planet—at least in crude

terms of overall population and global distribution. Should they be

grateful?” (RC, 23).

Should they be grateful? There is something perverse about

claiming that species that literally have no access to almost all of

their natural behaviors (dust bathing, companionship, foraging,

grazing, sexual contact, raising of one’s babies, etc.) are successful.

The idea that the enormous number of domesticated farm animals

constantly living and dying is somehow a boon to these species

seems ludicrous and is a misuse of the idea of evolutionary success.

True, there are billions of farm animals on the earth every year, but

their individual lives are fi lled with suffering and frustration from

the day of their birth till the day of their slaughter.

Of course, Fearnley-Whittingstall and Pollan’s point is that fac-

tory farms and the suffering they cause are a terrible breach of this

contract. As an argument, however, this is contradictory. They both

cite high population as proof that these species have become successful

with our help, but in the same breath they declare that factory

farms, which are the main reason for such high populations, are

a breach of this contract. Fearnley-Whittingstall says this of factory

farms: “This isn’t husbandry. It’s persecution. We have completely

failed to uphold our end of the contract. In the face of such abuse,

the moral defense of meat eating is left in tatters” (RC, 25).

The only reason there are so many domesticated farm animals

on the planet is that humans are constantly breeding them (many

can no longer breed on their own, and the vast majority are bred

by factory farms and the related animal industries). So if a species’

evolutionary “success” is really what matters (and justifi es our exploitation

of them), how can Fearnley-Whittingstall and Pollan

argue against factory farming practices and for small, sustainable

local farms, which will inevitably and drastically reduce these species’

populations?

For now, let us leave this contradiction and proceed from their

assumption that this contract is benefi cial. Most small farms are

not as conscientious regarding animal contentment as Salatin’s and

Fearnley-Whittingstall’s, but even if we use these farms as the example

of how things could be, we are still confronted with ethical

questions. On the best of these small farms, animals aren’t tortured.

They live decent lives, even pleasurable ones. They are fed,

have companionship, are given shelter and veterinary care, and live

in environments that are appropriate for their behaviors and needs.

They are, however, still often branded, castrated, have their babies

culled or used for veal, and are killed when they are no longer

productive. They are killed when they have years of life to live, as

animals are almost always sent to slaughter when still very young.

They are still emotional, sentient beings who are nothing more

than property—a cow reaching weight to become a steak to sell.

Do humans have the right to make other living and sentient beings

into objects of production that we can kill even when it is unnecessary

to do so, merely for our pleasure? Even if the animals die

quickly on their home farm (a rarity for larger meat animals, who

must legally be sent to certifi ed slaughterhouses), what justifi es this

killing? How are we justifi ed in ending a life of happy contentment

to satisfy a passing craving?

Here’s Fearnley-Whittingstall: “Pro-meat arguments based on

habit, health or survival, persuasive though they may feel to their

protagonists, do not really bite on a pragmatic level, let alone in

the realm of pure ethics. At best, they establish the self-evident fact

that the human race is, and has long been, meat eating. But we carnivores

must also concede that, in all but a few extreme environments,

meat is not essential for human survival or even for good

health.” So if religion is not an acceptable justifi cation for meat

eating, and neither are habit, health, or survival—and this coming

from someone who makes his living off of slaughtering animals—

then what is? Is this co-evolution theory convincing enough to justify

continued and unnecessary slaughter?

I will argue momentarily that this contract is not ethical in the

fi rst place, but for now I want to point out that even if we accept

this evolutionary contract and its symbiotic relationship between

humans and domesticated animals as a valuable concept, we must

still reevaluate how and what is important about this relationship.

On these small farms, slaughter is actually a deep breach of trust

between the interdependent beings who are mutually supporting

each other. After all, these animals do far more for us than just

give us meat: they care for our soil, feed our plants, and enrich our

lives as friends and companions. In fact, according to Fearnley-

Whittingstall, Salatin, and Pollan, we could not grow food sustainably

without these farm animals. This leads us to the biggest

problem with the co-evolution argument: the evolutionary bargain

is simply unequal. We care for these animals, and they in turn care

for our soil and land, making it possible for us to grow our plantbased

foods. This is the symbiotic relationship. But instead of appreciating

the mutual relationship we have with these animals, we

charge them an extraordinary extra cost—their lives and the lives

of their children. We breed them as we deem fi t, eat their babies,

and then, when we no longer see them as animals but as meat, we

kill them. The above farmers and writers may agree with this bargain

as it’s been philosophized by those who eat animals, but if the

tables were turned and we were offering up our babies and fl esh,

no doubt the inequality of the theory would quickly be determined.

Whether this contract was fair in the fi rst place is in many ways

the most important question. Nussbaum’s critique of the power

asymmetries in a state of nature is even more pertinent here. To

argue that animals were on a level playing fi eld with human beings

when this supposed contract was made ignores the obvious fact

that humans and animals have extremely varied mental and physical

capacities. This bargain was not made between beings “roughly

equal in mental and physical power,” but between powerful human

beings and more vulnerable animals. It is clear that this contract

was written by the more powerful human beings for their

own interests: under this contract, humans benefi t not only as a

species but also as individuals, whereas animals “benefi t” (if that

word can be used at all) only as species, not as individuals.

Fearnley-Whittingstall and Pollan argue that on some evolutionary

level the animals have agreed to slaughter, that because animals

have historically continued to stay around human encampments,

even when there were no physical fences and when they continued

to be slaughtered, this is proof that a relationship with humans

was worth death for them. But not all fences are physical. One

only has to look at the history of male domination over women,

the rampant and insidious nature of patriarchy, to see various fences

and barriers at work. One cannot argue that the domesticated

animal chose slaughter anymore than one could argue that women

chose patriarchy.

There is an aspect of trickery in the philosophy of the humane

meat movement. No animal would knowingly put herself in a situation

of danger. On Polyface Farm and many others, the farmers

and animals do have affection for each other, which Salatin,

Fearnley-Whittingstall, and others have openly talked about. But is

this affection misleading? Is it trickery? Is trickery of this sort unethical?

To bite the hand that feeds is part of a well-known idiom,

but perhaps it is more apt to speak of being killed by the hand that

feeds.

There is yet another problematic aspect to the contract theory

of co-evolution, and that is its reliance on the idea of dependency.

Fearnley-Whittingstall argues that we must kill animals because

they are now domesticated and dependent on us. They will be burdens

unless we get something in return—their fl esh. “Of all the

creatures whose lives we affect,” he writes, “none are more deeply

dependent on us—for their success as a species and for their individual

health and well-being—than animals we raise to kill for

meat. . . . We control almost every aspect of their lives: their feeding,

their breeding, their health, their pain, or freedom from it, and

fi nally the timing and manner of their death. We have done so for

hundreds of thousands of years, to the point where their dependence

on us is in their nature—evolutionarily hardwired” (RC, 31).

Dependency: a reason that has been used to justify slavery, patriarchy,

colonization, and disability oppression. Slaves were said

to be dependent on their “masters.” Pro-slavery rhetoric used the

supposed dependency of slaves as a justifi cation for their continued

exploitation. Women were said to be dependent on their husbands

and male society. This dependency was seen as being part of their

charm, a natural and preferred feminine condition. The language

of dependency is indeed a brilliant rhetorical tool, as it is a way for

those who use it to sound concerned, compassionate, and caring

while continuing to exploit the supposed subjects of concern.

Some may argue that animal dependency and disability dependency

are different from the above examples, because the descriptor

“dependent” is simply more “accurate” for animals and disabled

people. But dependence is relative and, as these historical

examples show, has everything to do with how society is arranged

and who is privileged. When women had no rights to income or to

partake in politics, their dependency (although not purely physical)

was both real and oppressive. Disabled people, the elderly, and

animals, although often more physically vulnerable than women,

are largely made dependent by a society that has not been arranged

with their rights and lives in mind.20

Whom is society made for? Some may argue that the fi nancial

burden of making society accessible, and of coexisting with animals

without profi ting off their fl esh, is unrealistic. I do not pretend

to offer in this text a reorganized national budget to do this.

But that is not the purpose of this essay, just as it was not the role

of nineteenth-century abolitionists to explain to a fearful public

how freeing the slaves would benefi t a fragile American economy.

As Nussbaum says, “theories of social justice must also be responsive

to the world and its most urgent problems, and must be open

to changes in their formulations and even in their structures in response

to a new problem or to an old one that has been culpably

ignored” (FJ, 1).

Society must take into consideration the lives of disabled people

and of nonhuman animals. And society will not come away from

this relationship empty-handed, as disabled people and nonhuman

animals have much to offer. Disabled people are often seen as being

inspirational and brave, but even this well-intentioned rhetoric

misses the point of disability studies and continues a discourse of

pity that is oppressive for disabled people. I argue, through a disability

studies and disability culture lens, that among many other

things, disability can offer new perspectives on such core concepts

as independence and embodiment. It offer new realizations

of physical and mental creativity and of community and support.

It would be impossible, considering the vastness of the animal

kingdom and its deep entanglement with our environments, to try

to sum up in a few sentences what nonhuman animals can offer

human beings. Suffi ce it to say that domesticated animals are at

this moment an integral part of our relationship with nature and

some would say with agriculture. It is time we stop taking advantage

of these animals who are currently doing so much for us beyond

providing animal protein.

It is important to note that there is a debate as to whether domesticated

animals are truly essential for sustainable plant-based

agriculture. Much of the humane meat movement argues that veganism

is naive in thinking we can grow sustainable food without

the use of domesticated farm animals. I am not a farmer, but I must

express my distrust of this argument, as none of the authors I have

written about above actually take on the possibility of veganic

farming (sustainable farming without domesticated animal products)

in any detail. I have never seen it mentioned by these authors

that in the United Kingdom there is a certifi cation process for what

is called “stock-free” farming, a viable and practiced form of ag-

riculture.21 Whether or not this form of farming is practical in the

end, I cannot help but question this large gap in the writing of these

authors who clearly are capable of thorough and fair research. I

also must question a certain lack of imagination surrounding the

possibility of sustainable vegan agriculture. Throughout history

people have managed to grow food under amazing circumstances

and in myriad ways. The fact that it has never been a human priority

to develop farming methods that don’t rely on animal products

(such as blood and manure) and that minimize harm to fi eld animals

(who often die during farming processes) says more about the

paradigm of human domination over animals than it does about

the viability of developing a sustainable and vegan agriculture.

The more signifi cant question for our purposes, however, is

whether killing is necessary and justifi ed under our current agricultural

methods. When proponents of humane meat argue that we

need domesticated animals for sustainable agriculture, they fail to

mention that slaughter is not a necessary component of this need.

Animals do not need to be killed to poop. In fact, our constant

cycle of breeding, killing, replacing, breeding, killing, replacing

seems like a terribly ineffi cient way to go about accessing manure.

If people really only ate meat for plant-based agriculture, surely

someone would have reminded them of this one golden rule: animals

still poop in their old age. In fact, most of the positive effects

animals can have on crops and soil comes from the very fact that

the animals are alive. The one exception to this may be in the common

practice of using blood, bone, feathers, and other discarded

animal parts as compost. However, even this use seems to not depend

on killing so much as on the simple inevitability that animals

die (and despite claims to the contrary, vegans are not opposed to

death, but to unnecessary killing).

The claim that humans should, in some way, continue to have

an interdependent relationship with domesticated animals is not

a very common vegan argument. Many vegans argue that the responsible

thing to do with these animals is to stop breeding them.

In a way, I understand why the prospect of having these species

(that humans have bred to be vulnerable, dependent, and pretty defenseless)

go extinct seems like the most responsible answer; after

all we’ve done, why should we be trusted as caregivers? However,

I disagree that it is necessarily the ethical and responsible thing to

do. For one thing, I think the problems brought up throughout

this essay surrounding issues of dependence are relevant. People

often make gross misjudgments on quality-of-life issues about disability

and jump to conclusions about which lives are worth living.

We must question these assumptions as they relate to animals as

well. An animal may be dependent, but what does this dependency

really mean? Is an animal’s dependence simply a negative condition

that makes her vulnerable to exploitation, or is this dependence

actually more closely related to interdependence, in which

humans recognize the value of a relationship with these animals

beyond a simple calculation of mutual advantage? Could the dependence

of domesticated animals be seen as an opportunity for

humans and animals to coexist, as humane meat supporters say,

“symbiotically,” but without exploitation? I argue that for humans

to stop treating animals as exploitable “things,” we must actually

continue to have relationships with them, relationships that are not

shaped by ownership (pets), spectacle (zoos), or exploitation (eating

them), but by interdependence, where we recognize, value, and

respect the help they give us and their right to live.

Of course, precisely how such a relationship would work and

how much of a role humans would play in these animals’ lives

must be considered seriously, and I won’t pretend to have the answers

in the remainder of this essay. The question of population

would perhaps be the greatest challenge to this relationship, as

culling to keep the population down would no longer be an acceptable

option, but clearly population explosion would need to be

avoided. Currently, humans breed virtually all domestic animals.

What relationship would we have to these animals’ reproductive

lives? How could we be sure that these animals would not just

be exploited as property again under a new guise? The questions

brought up by this human and animal relationship would no doubt

be complicated, but I believe it is worth considering such questions

and scenarios as possibilities for how a paradigm shift toward animals

might work and what it might look like.

I have been focused here on issues of dependency and domesti-

cation, but a fuller consideration should also take up the humane

meat movement’s other main point of contention with animal

rights: nature. Pollan, Fearnley-Whittingstall, and the movement

they represent argue that vegans and vegetarians “betray a deep

ignorance of the workings of nature” (OD, 322). Fearnley-Whittingstall

seemingly accuses vegans and vegetarians of wanting to

deny death, by reminding us that animals will never be “immortal”

(RC, 18). Pollan accuses us of wanting to “airlift” humanity and

all the other carnivorous animals out of “nature’s ‘intrinsic evil’”

(OD, 322). They both accuse us of ignoring “the natural order of

things.” To me, such statements indicate these authors’ ignorance

of the ideas and philosophy of veganism and animal rights, which

are not opposed to death and are defi nitely not anti-environmental.

Sustainability and environmental justice are basic tenets of animal

rights philosophy. After all, nonhuman animals need this planet to

survive just as much as humans do.22

The knowledge that farmers have about nature is no doubt powerful,

informative, and important, and I in no way discount that.

But it is not the only lens through which to view nature. Phrases

such as “the natural order of things” cannot be separated from human

culture and biases. “To think of domestication as a form of

slavery or even exploitation,” Pollan says, “is to misconstrue that

whole relationship—to project a human idea of power onto what

is in fact an example of mutualism or symbiosis between species”

(OD, 320). But where does Pollan think our understandings of

nature come from? They come from human conceptions, conceptions

that are inevitably biased and have grown out of a certain

paradigm of human domination over animals. The distinction Pollan

makes between a “human idea of power” and a natural state of

“mutualism and symbiosis” seems deeply problematic, especially

when one considers that slavery and patriarchy were both seen as

simply natural at one time. The difference between the rhetoric of

historical forms of human exploitation that were rooted in an idea

of “natural order” and the rhetoric of our current system of nonhuman

animal exploitation that is rooted in an idea of “natural

order” is that it is still considered justifi able to exploit animals. By

criticizing the humane meat movement’s use of the idea of nature,

I am not denying the validity of their farming methods or their

knowledge of nature; rather, I’m denying that their view of nature

is the only view and an unbiased one.

As I have discussed, “nature” has also been a predominant justifi

cation for the continued oppression of disabled people. Reliance

on farmers (such as Salatin, Fearnley-Whittingstall, and Hahn Niman)

as “experts” who understand animal nature parallels the reliance

on doctors as the experts on disability. While these “experts”

have great knowledge about certain aspects of the nature of disability

and the nature of animals, they are also deeply biased in the

way they see animals and disabled people and in the way they profit

from them. Both farmers and doctors are trained to “see” in a

certain way; they are both trained in specifi c paradigms of nature.

Most farmers don’t look at their animals for signs of intelligence,

compassion, individuality, emotion, or drive for life, and doctors

rarely see their disabled patients as whole, healthy, and fulfi lled

individuals (this I know from experience). A doctor may know every

detail about what can cause arthrogryposis or about what the

latest surgical options are for correcting aspects of it, but a doctor

knows nothing about disability culture, the disability rights movement,

about the “social model” of disability versus the “medical

model,” or about how my disability has positively affected my creativity.

Of course, there are exceptions—doctors who understand

disability as a civil rights issue and farmers like Salatin who know

many of their animals individually. But even Salatin is caught in

a specifi c paradigm, a paradigm in which he is unable to imagine

that animals may have souls. It seems problematic that the very

people who are in many ways leading certain aspects of the conversations

around both disability and animal advocacy are those who

are profi ting from the continuation of these oppressive paradigms.

Conclusion

Do animals deserve equal consideration? Do their experiences matter?

Do our desires to eat them instead of eating other available

foods outweigh their desires to stay alive?

I have focused on issues of humane meat throughout this essay,

not because it is a better example of the connections between disability

and animal rights than in the broader animal rights conversation,

but because it is the most prevalent and well argued of the

contemporary anti-animal-rights discussions. The humane meat

debate and its support of animal welfare also exists as an interesting

counterpoint to the idea that disabled people are in need of

charity and welfare versus being deserving of equal rights in access

to housing, education, careers, social opportunities, and so forth.

The similarities and parallels that exist in the rhetoric and language

of proponents of animal welfare and the charitable organizations

that “help” the “handicapped” are striking. The idea of helping

those who are dependent is prominent within both lines of thought,

but rarely is it ever asked what social injustices make these groups

dependent and how these injustices could be rectifi ed. It is presented

as simply natural that these groups are in need of help and it is

emphasized that they can’t help themselves. Both lines of thought

use the rhetoric of pity to gain support for their cause. Both lines

of thought advocate for better treatment and more sympathy, but

usually shy away from suggesting a broader struggle of oppression,

inequality, discrimination, and the need for justice, not charity.

There is no doubt a limit to how far these parallels between

disability studies and animal rights can go. They are vastly different

forms of oppression in many ways. Many might say that

this sort of comparing of oppressions is not helpful, as it simplifi es

the complex issues that each group individually faces. As much as

I agree that these differences must not be forgotten, I also think

the existing parallels could be valuable to both fi elds; to shy away

from them would be unproductive and have the effect of closing

off potentially valuable areas of dialogue and thought. Throughout

this essay I have thus argued that examining these two subjects together

reveals many important intersections that have the potential

to push both fi elds in necessary and challenging ways.

One of my most recent paintings, Animals with Arthrogryposis,

shows an image of myself standing nude (my posture bent, some

would say like a monkey), with two factory farm pigs and a calf

(fi g. 4). The image is large, six feet by nine feet (oil on canvas,

2009). In the image, yellow medical arrows point to each of us.

The image is reminiscent of a medical photo, and we are numbered

A–D. The full name of my disability is arthrogryposis multiplex

congenita. The animals shown in this painting have the same disability

I do. In cows the condition has its own name: curly calf.

Pigs, cows, lambs, and numerous other animals can also have this

condition, and it is found often enough on factory farms to have

been the subject of Beef Magazine’s December 2008 issue.23

I say this not because I think disability should make us more empathetic

to these animals but to show just how closely we are like

them. Of the 50 billion animals that are killed every year for human

use, the majority are literally manufactured to be disabled—

bred to be “mutant” producers of meat, milk, and eggs.

This essay has tried to present a case for why disability and animal

rights should be taken seriously as social justice issues, while

simultaneously hoping to challenge the fi elds of disability studies

and animal rights to take each other seriously. By showing how

disability studies reevaluates the meanings of such loaded words

as “independence,” “nature,” and “normalcy” and by exploring

the ways in which disability studies demands new perspectives on

embodiment, this essay has presented an argument for why disability

studies needs to incorporate nonhuman animals into its

framework, as these reevaluations affect nonhuman animals just

as much as, if not more than, they do disabled people. I argue that

disability studies is left in a state of contradiction if it claims to

fi nd value in differing bodies and minds, different ways of being,

but then excludes nonhuman animals. Although many infl uential

theories of justice and equality are already incomplete in leaving

out nonhuman animals, I argue that disability studies, because of

its particular values, has an even more urgent responsibility to consider

justice toward nonhuman animals.

I acknowledge that there are areas in which the needs of disabled

people may bump heads with the needs of nonhuman animals

(such as in certain dietary and health requirements or in the

use of nonhuman animals to test drugs that will be used to treat

illnesses and impairments). It must also be acknowledged that asking

persons in the disabled community, an extremely marginalized

group, to potentially marginalize themselves even farther by in-

cluding nonhuman animals is a lot to ask. These issues must be

considered thoughtfully. Despite these valid complications, however,

ignoring issues of justice toward nonhuman animals will leave

disability studies in a contradictory position. What’s more, it will

support an unjustifi ed paradigm of human domination and abuse

toward billions of nonhuman animals.

Notes

1. Exploring factory farm imagery in my artwork came naturally, as

animal rights and environmental issues had always been of concern

to me growing up. My siblings and I became vegetarian by choice as

young children when, as we put it, we learned that “meat was animals.”

During this time we would often see huge trucks loaded with

hundreds of cramped chickens driving down the highway. When I

learned as an adult that I unknowingly lived a few blocks away from

a chicken-processing plant (the fi nal destination of these trucks), I

quickly decided that I wanted to use the opportunity to photograph

one of these trucks as it was stopped outside the plant (these trucks

never stop in public locations). These photos led to a series of paintings

of animals in factory farms, which I worked on throughout my

time in graduate school in the Department of Art Practice at the University

of California, Berkeley.

2. Rosemarie Garland Thomson, “From Wonder to Error—A Genealogy

of Freak Discourse in Modernity,” in Freakery: Cultural Spectacles

of the Extraordinary Body, ed. Thomson (New York: New York

University Press, 1996), 4. Hereafter cited as “FWE.”

3. The term “nonhuman animals” and the more effi cient but less accurate

term “animals” will be used interchangeably in this article to describe

all animals but human beings, except in places where the word

“animal” is clearly being used to describe all of us.

4. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, “Circuses,” http://www

.peta.org/issues/animals-in-entertainment/circuses.aspx.

5. Stephanie Ernst, “Animal Use and Abuse Statistics: The Shocking Numbers,”

http://animals.change.org/blog/view/animal_use_and_abuse

_statistics_the_shocking_numbers.

6. Paul K. Longmore, Why I Burned My Book and Other Writings on

Disability (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2003), 222.

7. Peter Singer and Jim Mason, The Ethics of What We Eat: Why Our

Food Choices Matter (Emmaus, PA: Holtzbrinck, 2006), 130–31.

Copyright © 2011 Qui Parle, not for resale or redistribution

Taylor: Disability Studies and Animal Rights 221

8. There is debate as to whether animals such as oysters, who lack central

nervous systems, are sentient. See Christopher Cox, “Consider

the Oyster: Why Even Strict Vegans Should Feel Comfortable Eating

Oysters by the Boatload,” Slate, April 7, 2010, http://www.slate

.com/id/2248998; and Marc Bekoff, “Vegans Shouldn’t Eat Oysters,

and If You Do You’re Not Vegan, So . . .” Huffi ngton Post, June 10,

2010, http://www.huffi ngtonpost.com/marc-bekoff/vegans-shouldnteat-

oyste_b_605786.html.

9. Martha Nussbaum, Frontiers of Justice: Disability, Nationality, Species

Membership (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006). Hereafter

cited as FJ.

10. Martha Nussbaum, “Justice,” in Examined Life: Excursions with

Contemporary Thinkers, ed. Astra Taylor (New York: New Press,

2009), 118. Hereafter cited as “JU.”

11. Nussbaum offers a solution to these problems with a theory of justice

she has developed called the Capabilities Approach in FJ.

12. Although many authors take up this theory, Stephen Budiansky fi rst

popularized it with The Covenant of the Wild: Why Animals Choose

Domestication (New York: Morrow, 1992).

13. Michael Oliver, The Politics of Disablement (New York: St. Martin’s

Press, 1990), 91.

14. Some of this section has been taken from my article “The Right Not

to Work: Power and Disability,” Monthly Review, March 2004,

http://www.monthlyreview.org/0304taylor.htm.

15. Michael Pollan, “The Ethics of Eating Animals,” in The Omnivore’s

Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals (New York: Penguin,

2006), 304–34 (hereafter cited as OD); Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall,

The River Cottage Meat Book (Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press, 2007)

(hereafter cited as RC).

16. Nicolette Hahn Niman, “I Am a Vegetarian Rancher,” in Eating

Animals, by Jonathan Safran Foer et al. (New York: Little, Brown,

2009), 207.

17. Some of this paragraph has been taken from an article I wrote with

Alexander Taylor called “Is It Possible to Be a Conscientious Meat

Eater,” February 18, 2009, http://www.alternet.org/story/127280/

is_it_possible_to_be_a_conscientious_meat_eater.

18. See the work of legal scholar Richard Posner.

19. Fearnley-Whittingstall’s version of this theory comes from Stephen

Budiansky’s The Covenant of the Wild (see n. 13).

20. I want to again make clear here that I am making a distinction be-

Copyright © 2011 Qui Parle, not for resale or redistribution

222 qui parle spring/summer 2011 vol.19, no.2

tween physical autonomy and independence. Someone who is quadriplegic

may not be physically autonomous in the same way an ablebodied

person is, but this is not necessarily what makes this person

dependent. If this person has access to the social services he or she